I’ve wanted to write a diet based blog for a while, but I’m always reluctant to wade into the public conversation to oversimplify what can be a complicated topic. Especially in the New Year where there is so much reductionist crap in the media. It’s a time of year that frustrates the hell out of me to be honest. Everyone seems to be on their soap box with their latest soundbite to fix everyone’s dietary problem.

So, with this backdrop in mind, I’ve decided to focus my thoughts on the least controversial and perhaps most powerful aspect of your daily diet. Something that you might not have even thought about. Because I am a coward and I don’t have time here to cover everything.

This blog is an introduction to the idea that WHEN you eat really matters.

I want to start by borrowing a nice little diagram from Dr. Peter Attia, one of several Americans I follow because of their expertise in intermittent fasting/time-restricted feeding. I’ll come onto exactly what that is in a bit, but I want to use Peters handy little tri-axial diagram as a starting place for the discussion.

In this diagram, the X axis represents WHAT you eat, the Y WHEN you eat, and the Z HOW MUCH. Dr. Attia argues that you need to be “pulling on” or restricting at least one and preferably two of these axis’ if your goal is optimal health and fitness/longevity. The implication being that if you aren’t conscious or aware of your diet at all and are eating a standard western diet you are unlikely to be healthy, fit, or live very long.

For those mindful that the modern diet is often not a healthy one, a proactive approach is one where you restrict your diet in some way with either WHAT you eat (on the X axis), WHEN you eat (on the Y axis) and/or HOW MUCH you eat/calorie restriction (on the Z axis).

Are you with me so far?

Most talked about in this triangulation is definitely HOW MUCH TO EAT - the calorie angle, because people are getting fatter and it’s because they eat too much. People are just greedy aren’t they. Oh, and lazy. People are just greedy and lazy. Everyone just needs to exercise more and eat less to stay lean and be in shape.

Now there’s plenty of evidence that this “energy in – energy out” model is biologically incorrect, but it’s still likely your doctor will favour this approach if you’re overweight, and it’s a myth still pushed by the main stream fitness and sports media too. In my view that’s the first glaring over simplification and massive untruth about diet still floating around in the ether, even though it’s been proved wrong time and time again.

But since that’s a whole minefield on its own, I’m going to move onto the other aspect of diet most widely discussed and debated – the WHAT to eat. And here too lies a lot of the confusion for many people. Don’t eat fat, do eat fat, carbs are good for energy, carbs are bad, meat is bad, vegetables are good, etc. etc. …blah blah…. I could go on. But we’re going to park that one too for now and move onto the third key element that I want to focus on here.

Until very recently there hasn’t been much discussion about WHEN to eat, and what impact that might have on your health, fitness and longevity. And here I believe I’m onto a winner, because I think we can all agree that you shouldn’t eat ALL THE TIME. That would be ridiculous. So how can we work with this common sense, straight forward idea to exploit it for our gains without needing to focus too much on what we eat and how much.

In its simplest form, ‘time restricted feeding’ is exactly what is says it is. Not eating all the time. And ‘intermittent fasting’ is really the same thing. Sometimes you’re eating, and when you’re not eating, you’re fasting. Simple.

So the first thing to reflect on is how often are we actually eating? How long is our eating ‘window’ in any 24 hour period, and how far have we come from our optimal biological norm?

Now there would have been a time not all that long ago when most people ate 3 meals a day. They finished their dinner at 7, slept 8 hours at night and had a civilized start in the morning, perhaps breakfasting at around 8am. Going back further still it’s reasonable to assume there would have been times in our primitive history when we would have gone for fairly long periods without food, and been biologically designed to cope with that.

These days most of us have come a long way from the way things were even 50 years ago let alone thousands of years ago. Our ‘eating window’ can stretch well into the evening when its dark outside, working lunches have been normalised and the importance of ‘snacking’ to keep our energy up has been literally shoved down our throats at every possible opportunity. We often eat on the move, not even bothering to sit down while we’re grabbing our snack, and if you think I’m exaggerating take a look at how often you eat during your day and how long your own personal eating window lasts. Literally write down the time that anything and everything goes in your mouth. Drinks included. Better still, use a twitter photo diary as I do with my clients, and as I explained in my previous blog back in May 2015.

https://www.jomcrae.co.uk/blog/twitter-feeding

I know that for me when I started using a twitter food diary to evaluate my diet what struck me most was how often I was eating. Due to the nature of my work, keeping strange hours and being on the move a lot I was often not at home at typical meal times, so I found that my day had become one great big snacking fest. It was not uncommon for me to eat every couple of hours between appointments, having something small instead of a proper meal, and as a result probably something less than ideal too. I might eat first thing at 7/8am and then still be snacking at the end of my day between 9 and 10pm.

Back in May 2015 here was my review of my diet:

1. A lot of the food I eat goes straight to my mouth without landing on a plate.

2. If I don’t stop to eat a proper meal at roughly the right time of day, I am very likely to eat frequently because I have never really had enough of the right foods to last for several hours.

3. When you have to stop and take a photo of everything you are eating, you tend to want to make it look nice and fresh, and when it looks nice and fresh it usually is a lot more nutritious.

Now some people might normalise this by saying “Oh, I don’t like big meals”, or “I prefer to graze”, or “I’m an athlete, so it’s important I keep my energy up”. But from a biological/digestive point of view this pattern is a disaster. Put simply, your poor gut never gets a rest. Something is always on the way through. And your hormonal systems are being horribly overworked too, with your pancreas having to respond to every mouthful, releasing insulin to drive glucose from the blood into use or storage.

‘Primal movements’ have been trending in fitness for years, and in a way intermittent fasting is the obvious dietary companion to the same notion - that treating our bodies in the way they are designed to work will lead to optimal health and performance. This is the biggest lesson that 20 years of working in sport, fitness and health has taught me.

There are of course strong arguments to move towards a more primal diet in terms of what we eat too, but the fact is that for many people that can overcomplicate food choices and represents a much harder behavioural change. In contrast getting a grip of when you are eating and beginning to manipulate that can be relatively straight forward. Food shouldn’t be available to us 24/7. That just isn’t ‘natural’, and yet it has become normal. So if we want to improve our health, perform better, and perhaps lose weight, we need to ensure there are significant gaps in our day when we are not eating.

One of my favourite resources to share with clients on this topic is Jason Fung’s you tube presentation on the 2 compartment model. Fung is a specialist in treating obesity and Type II diabetes with prolonged fasting and a low carb approach, and in this presentation he dispels the calories in - calories out model. He summarises the behavioural benefits of fasting by dispelling many of the common barriers to making a dietary change, making the point that you can add fasting to any diet.

..”You can still fast…..” says Jason Fung

For those sports people among the readers the idea of fasting might be particularly challenging. We have been told that we need to replenish our glycogen at every opportunity, snack before we are hungry on long endurance efforts and ensure we are ‘refeeding’ carbohydrate in the first hour after exercise. Some cyclists might be aware of the benefits of fasted training in the morning, but for the most part the mainstream mind set is still to ‘top up’ on carbohydrate gels and sugary snacks every 30 minutes.

For many people who are ‘mainstream’ amateur athletes whether fasted training is a good idea or not I would argue that the need for constant snacking is questionable and in many cases, can drive insulin resistance. Being mindful of the fact that there is a whole snacking industry targeting you that calls itself ‘sports nutrition’ is a good place to start when you are trying to strike the balance between robust health and sports performance. I have seen clients snack after a Pilates class because of the ‘refeeding’ mindset, when - let’s be honest - you are not at risk of glycogen depletion and you can probably quite safely wait for your next meal.

Most of the sports people I work with are amateurs, and for many it’s worth emphasising that we are humans first, and ‘athletes’ second, evaluating any marginal gain in the moment from ‘sports nutrition’ intervention weighed against any long-term damage their frequent use might cause. If this idea resonates with you, I would urge you to look at the work of Dr. Tim Noakes in dispelling the myth that a high carbohydrate, heavy snacking diet is essential for optimal endurance performance.

I make these points to show that I’m aware that there is still some controversy around some of the more prolonged fasts for sports people and their impact on performance, and also that there is some debate as to whether longer fasting is appropriate for female athletes in particular. So let me be clear on what I’m talking about as a suggested starting point here.

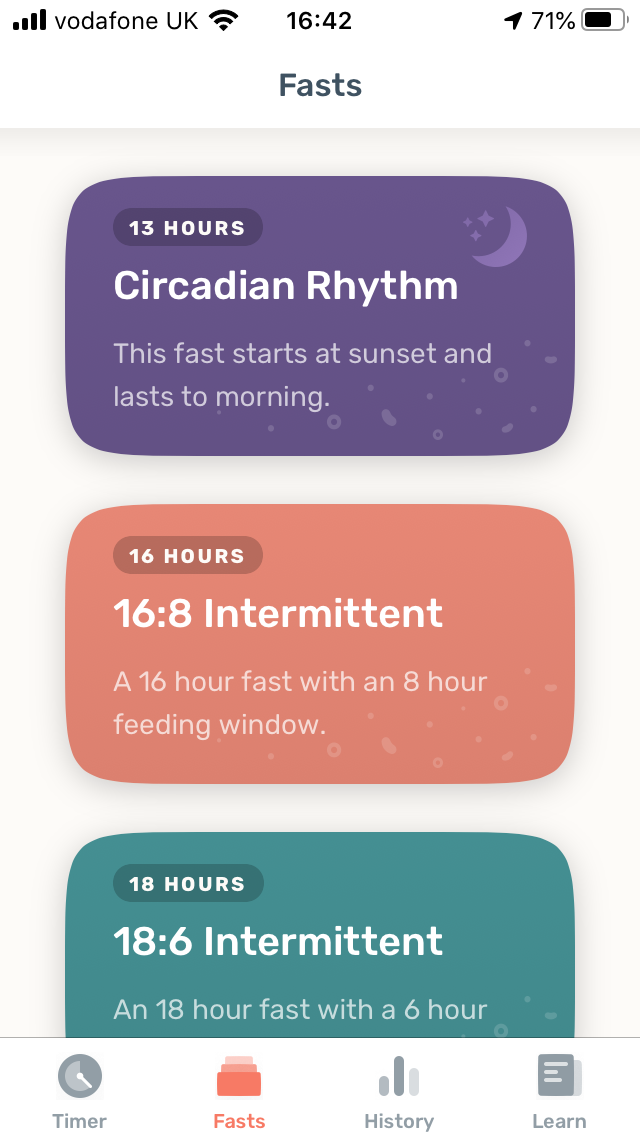

Is your fasting window over 24 hours bigger than your eating window? In any 24 hour period do you allow your body to recover for at least half of the time there is food going in? Because for many of us (me included) this is a good place to start. The 13 hour ‘circadian rhythm’ fast simply restores the normality of not eating for 13 hours and eating during the other 11.

I’ve been using the “Zero” app to log my eating/fasting patterns and to try to improve them.

And the good news is that the research suggests that this is enough to give you a whole host of big health benefits. My favourite current discussion on the topic is a podcast conversation between Dr Rangan Chattergee and Dr. Satchin Panda, author of the book ‘The Circadian Code’. In it Dr Panda discusses his clinical research on mice that showed that an eating window of 11-12 hours protected mice on a ‘poor diet’ from developing obesity, type II diabetes, high cholesterol and cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, in Panda’s experiments mice that were restricted to an eating window of 8 hours a day almost doubled their performance on an endurance treadmill test. Now, ok, we’re talking about mice here, but these exercise findings are consistent with trends in ultra-endurance events where some athletes are taking the time to adapt to a ketogenic diet and reduced eating window to enhance their fat burning metabolism. I have experimented with his myself over the last year and felt good and have performed surprisingly well. But I’m not suggesting this for everybody.

Dr. Panda’s research also shows that 50 % of people in ‘westernised’ countries eat for 15 hours of the day or longer, so no wonder we have an epidemic of health problems. For most of us, even making a change to bring our eating patterns back to a more bio-logical 11/12 hours would be a great move in the right direction

In my experience working on my own diet and encouraging clients to work on theirs, this research has been borne out by the improvements you can feel in digestive health, blood sugar control, weight loss and energy balance. For many people (like me), increased awareness of long days that can include eating late and starting early can be enough to encourage a change in the time of your ‘break-fast’ that has a profound effect on your health. Avoiding snacking and focussing on whole food based proper meals instead is often a good place to start. Personally, I am working with a minimum of 13 hours and some days waiting till lunch to break my fast at 16 hours. I feel better, I can exercise with no problems, and my weight is well controlled without a lot of effort.

For some of my clients simply looking at the gaps between meals in the day is a revelation. For many people eating no more than 4 times a day is a significant change. The mini-fasts between meals can be a positive change too; one which makes you think more carefully about your daily eating routines and ensures you make time to eat something nutritious at an appropriate time on a regular basis.

In my coaching experience I have seen different benefits come with different approaches where clients have differing goals. One client who was forcing down breakfast because its the ‘most important meal of the day’ has just learnt to skip it and feels much better as a result. For some people this can be an easy way to avoid kick starting the day with some of the often heavily marketed highly processed ‘breakfast foods’ that have become traditional morning fare. Several who are looking to lose significant amounts of weight have successfully introduced a one meal a day (OMD) strategy for one or more days a week with relative ease, after practicing by first waiting till lunch. For all an increased awareness and some consistent practice have led to positive changes in health, fitness and well-being.

Perhaps most significant is the impact regular fasting has on the way you think about food. It’s common to find that you respect it more, because you think more carefully about what you’re putting in your mouth at meal time. Your blood sugar control is often improved, which means that you may be hungry, but you’re not hangry. And perhaps best for some busy people – you buy some time back when you are not thinking, preparing or obsessing over food. It feels good to be in control, and it feels natural. If you haven’t yet considered the WHEN of your eating habits, I urge you to try it and see what happens.